Marching Band

We Are Family

While the Chargers marching band has grown dramatically over the past decade, its devoted musicians — now 270 strong — have formed a powerful bond.

ALUMNI MAGAZINE

These are the stories behind the University of New Haven’s newest school — one that prepares students not only for the healthcare careers in demand today, but for the healthcare opportunities of the future.

If becoming a solar photovoltaic installer — the fastest-growing profession from 2016 to 2026, as projected by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics — is not necessarily in your five-year plan, don't fret. You still have options.

Jobs in the Health Services field — medical assistant, nursing assistant, and home health aide, for example — are expected to grow 19% by 2024, faster than most other professions. By 2025, the U.S. healthcare system is expected to account for one fifth of the national economy.

In Connecticut, health-related careers are expected to be the third-largest occupational sector by 2024, with over 30,000 healthcare jobs expected to be added. Of those, 42.6% will be in south-central and southwest Connecticut.

Summer McGee, Ph.D., CPH foresaw greater opportunities in health services as far back as 2015, when she served as chair of the University of New Haven’s Department of Health Sciences. "I’m a builder," Dr. McGee says. "I envision something incredible existing where before there was nothing. I’m constantly looking to shape or form or create something new that can stand the test of time."

"I’m a builder. I envision something incredible existing where before there was nothing. I’m constantly looking to shape or form or create something new that can stand the test of time."Summer McGee, PH.D., CPH, Dean of School of Health Sciences

So McGee spearheaded the creation of the University’s newly established School of Health Sciences (SHS), which officially opened for business this fall, with McGee as the founding dean. The University’s newest school is the culmination of nearly three years of collaboration and planning by more than 25 faculty members across all schools and colleges at the University. Their strategizing took place in a University-wide "virtual" department, the Department of Health Sciences, which existed outside of any single school or college and served as the home for the creation of new health-related degrees, research collaboration, and student support, among other services.

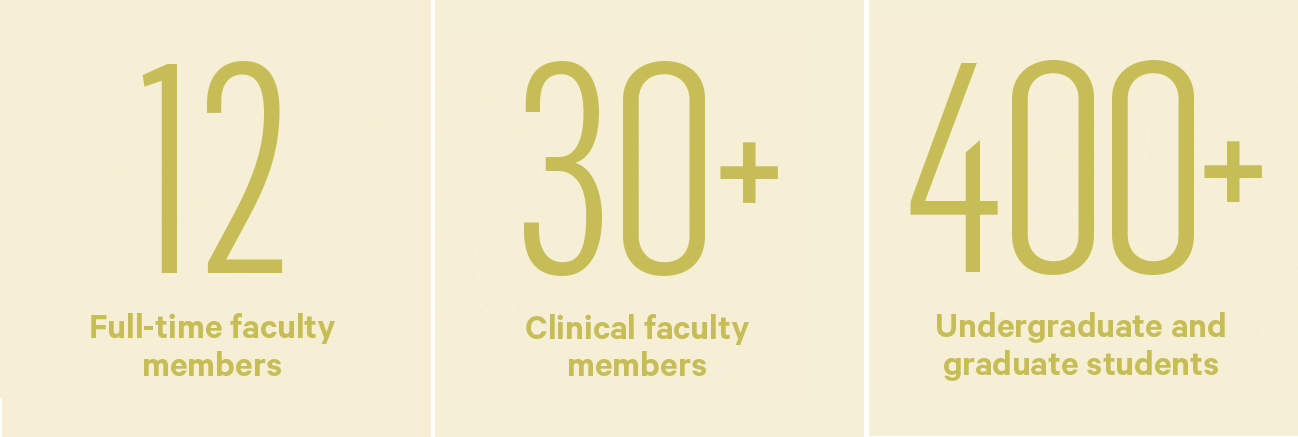

SHS comprises three University departments — Allied Health, Nutrition Sciences, and Health Administration and Policy — as well as the University’s programs in Dental Hygiene, Healthcare Administration, Health Sciences, Nutrition and Dietetics, and Paramedicine. There will be 12 full-time faculty members, more than 30 clinical faculty members, and more than 400 undergraduate and graduate students, in addition to doctoral candidates.

A nationally recognized expert in health policy, management, and bioethics, McGee joined the University of New Haven in 2013. She has also been recognized as a "Woman of Innovation" by the CT Technology Council’s 2017 Women of Innovation program.

It was this creative will that helped her push through the more difficult phases of bringing the School of Health Sciences to life.

"The term innovation is more than a buzzword," McGee says. "It’s a state of being. Challenges, whether social, organizational, or cultural, are opportunities for creation and growth. You need to flip the script and see solutions where, previously, others have only seen problems."

This mindset has resulted in some lofty goals. McGee and the SHS faculty aim to build a robust core curriculum across all health related programs at the University committed to inter-professional education; provide facilities and experiences that allow for real-world experiences; and grow health sciences program enrollments to 15% of the University’s total enrollment in five years (the equivalent of nearly 1,000 students). McGee notes that she aims for 90% of program graduates to be employed in the sector or enrolled in graduate programs within a year of graduating, and to attain a 100% board passage rate for licensed health programs.

"Creating SHS has been a leap of faith on the part of our students, faculty, and staff," McGee says. "President Kaplan and the Board of Governors are counting on us to put the University of New Haven on the map for health professions education. And now, we’re here. And all we need to do is jump."

Despite the chaos and complexity of bringing this dream to life, McGee keeps it simple.

"I can boil the mission and vision of SHS down to two words: growth and excellence," she says. "The SHS faculty live and breathe this ideal. They don’t think: What do we currently have in front of us? They think: What are we missing? They are passionate about their discipline and wholly dedicated to their students."

Here you will read just a few of a multitude of faculty stories that helped shape the vision for the future of health sciences at the University of New Haven.

Assistant Dean

School of Health Sciences

Associate Professor

Department of Allied Health, Dental Hygiene Program

Recognition

Bucknall Excellence in Teaching

The Dental Hygiene program at the University of New Haven offers students two experiential internship opportunities — one working with the Navajo Nation in Arizona, and the other in Prato, Italy. Garcia-Prajer, who developed both internships, says that these roughly two week-long trips help students hone their skills while also deepening their appreciation of different cultures.

There’s a significant need for dental services among the Navajos; students have full schedules throughout their stay providing preventive dental hygiene services, including the placement of pit and fissure sealants. In Prato, Tuscany’s second-largest city, students work with a local ambulance company, mentor first-year dental hygiene students at the University of Siena in the fundamentals of instrumentation, and assist in community and private dental practice settings.

Graduates are becoming dental hygiene program directors, oral health consultants, dental therapists, and even entrepreneurs. "A dental hygienist," Garcia-Prajer says, "isn’t just someone who works for a dentist and cleans teeth. There’s so much more to it."

LECTURER

Nutrition & Dietetics

INNOVATION

Helping launch one of the country's first "prehab" programs for liver and Pancreatic Cancer Patients

Stankus’ clinical work in the oncology department at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport, Connecticut, speaks volumes about the growing importance of registered dieticians.

In this role, he handles everything from intravenous feeding tubes to bimonthly cooking classes. In a new initiative, he’s helping to launch one of the country’s first "prehab" programs for liver and pancreatic cancer patients, working as part of a team to prepare them nutritionally, physically, and psychologically for surgery and radiation treatment.

Having the Nutrition program in the School of Health Sciences, he says, will make it easier to train students for these varied roles. One of the projects he’s working on at the University is setting up hospital-based nutrition assessment labs where students will work directly with patients, both from the University and the local community, on a regular basis.

"Students need to know how to make healthy meals that also taste good," says Stankus. As a former personal chef, he’ll make sure of that.

ADJUNCT FACULTY

Health Administration & Policy

PRINCIPAL

Summer Hill Associates, LLC

EXPERIENCE

Lobbyist for GE and Himss

Digital health, which encompasses everything from the latest fitness apps to new blockchain technology dealing with storing and accessing patient health records, will be a critical area of focus in the School of Health Sciences’ curriculum.

Griskewicz, who earned her master’s in industrial relations, is a sought-after authority in the health sciences field, having held health information technology leadership roles with insurers Aetna, Cigna, General Electric, New Haven’s Hospital of Saint Raphael, and the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.

As a lobbyist for GE and HIMSS, Griskewicz helped secure billions of dollars in federal funding to promote the U.S. healthcare system’s transition to portable electronic health records, an enormous logistical and policy challenge that’s still very much a work in progress. "We’re still not there yet," Griskewicz says, "but there’s new innovations coming out every single day."

In June, Griskewicz launched Summer Hill Associates, a consulting firm based in Madison, Connecticut, focused on patient advocacy and patient-centered IT strategies.

LECTURER, PARAMEDICINE COORDINATOR

Departments of Fire Science & Professional Studies and Allied Health

EXPERIENCE

Spent 13 years as Fire Chief in Wallingford, Conn.

As Struble explains it, the looming "silver tsunami" of aging Baby Boomers is going to make it increasingly difficult to get a hospital bed. As a result, paramedics will need to be equipped to manage cases in the field, so patients who don’t truly need to be seen in the emergency room can stay where they are or get care elsewhere.

It’s a concept called "integrated mobile healthcare," and it will require major changes in the way paramedics are trained.

The Paramedicine program Struble helped spearhead six years ago at the University of New Haven is well positioned to meet this challenge. It’s one of only a handful in the United States that offers a four-year baccalaureate degree. He believes that moving formally in 2019 to the School of Health Sciences will only make the program stronger.

In Struble’s day, paramedics didn’t need a college degree, but that’s where the profession is headed.

"They’re in the field by themselves and basically bringing the emergency room to the living room," Struble says. "There’s so much for them to know."

LECTURER

Department of Health Administration And Policy

UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM DIRECTOR AND FACULTY ADVISOR

Health Sciences

EXPERIENCE

Former Director of Mental Health Treatment Services in New York City

It’s a deeply troubling statistic: People with serious mental illnesses live 25 years less, on average, than the general population.

What’s shortening their lives so dramatically? "They don’t go to the doctor," Dr. Petitti says. The reasons for this, she explains, include poverty, health insurance issues, the debilitating effects of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression, and a shortage of primary care physicians.

A former director of mental health treatment services for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, who also has extensive experience as a consultant and top executive in the private nonprofit sector, Petitti is a leading authority on integrative programs that aim to address this public health crisis by combining primary medical care with behavioral treatment.

There’s a global dimension to her research: In addition to assessing the impact of recent federal funding cuts on integrative programs in the United States, she’s also looking at how other countries handle these same types of behavioral health challenges in terms of service delivery models for this specialized group.

While the Chargers marching band has grown dramatically over the past decade, its devoted musicians — now 270 strong — have formed a powerful bond.

Welcome to the newly established School of Health Sciences.

Former Chargers captain and current Board of Governors member Allen Love Jr. ’88, MPA ’90 lends a global perspective to the world of anti-money laundering.